THE POLLUTED RELATIONSHIP SPACE

RELATIONSHIPS & THE FOCUSING LENS OF COVID-19

FALLING APART, SORT OF: THE POLLUTED RELATIONSHIP SPACE

Don Edwards, October 2020

There has been a great deal of attention paid to the mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. It has disrupted relationships, social structures, workplaces and financial security. It has also challenged our confidence in governments and the stability of the public order and the economy, and raised questions about the legitimacy of governments to curtail individual liberties in the interest of the common good and/or the manner in which that is done. In the context of this article, the pandemic has become a catalyst to the collapse of even relatively stable relationships as well as to the increased incidence of child and elder abuse. Partners and families who have not been getting along particularly well have been forced to spend a great deal more time together, possibly in small living spaces that were not designed for 24/7 occupancy, not only as dwellings, but also as home offices and home schooling spaces. Priorities have gotten reshuffled during the pandemic, and conflict erupting in the relationship is not recognized as the consequence of this external stress being deflected by one partner onto the other. Partners may fail to realize how much they have relied on the relationship pressure valve function of being able to go to work outside the home, to school, to visit friends or to engage in leisure or volunteer activities outside the home. Without this pressure valve, the added pressure perhaps exceeds the strength of the relational bond. This article also references a range of couples therapy modalities because not every couple responds equally well to a particular modality. Having options will help the therapist serve a broader range of couples and couple problems.

WHY ARE WE TOGETHER IN THE FIRST PLACE?

“Staying together for the sake of the kids” is but one troubled couples scenario in which the original affectional glue that held a relationship together has been replaced by pragmatic incentives. The stable ambiguity of which Esther Perel speaks modulates the ambivalence of wanting to leave and fearing to go, as tacitly I love you has been replaced by I’m stuck with you, or the thought of living without you is worse than the reality of living with you.

In some cases the basis of being together was fragile from the outset. If chemistry was all there was in the beginning, all that is left when that fades is the awareness of difference as romance becomes roommates. In these cases once Eros has departed, Stan Tatkin’s famous question, what are you guys about as a couple? has no good answer. When people move in together fueled by desire and financial expediency, but with no real commitment, we have what David Steele calls a mini-marriage. Many people become cynical about relationships by having a series of these mini-marriages.

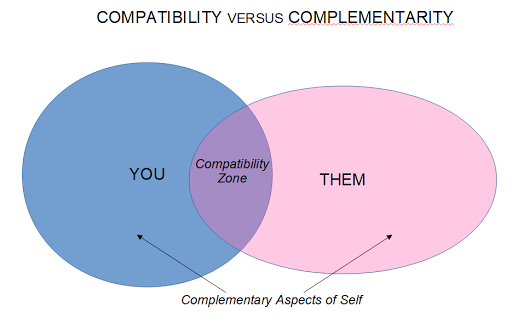

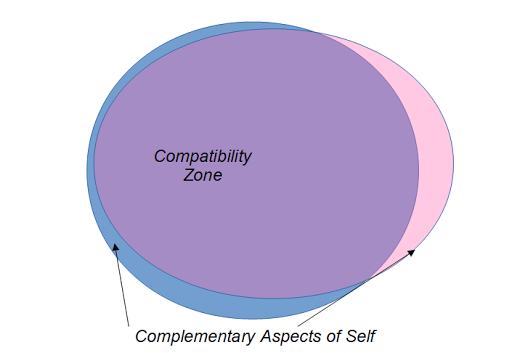

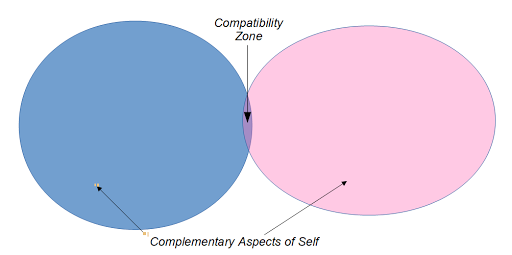

In understanding what makes a good partnership, it is helpful to distinguish between compatibility and complementarity – ideally, likeness versus synergy. A good partnership has a balance of connection through likeness and synergy through complementary differences. How we are similar and see ourselves in the other is our compatibility. How we add to each other or experience each other as different is our complementarity. If we seek the reassurance of the familiar, we crave more compatibility than complementarity. If we are repelled by our roots, we are attracted to what complements us because similarity may shame us. The choice of novel or dissimilar may be intentional. If we are secure in our self esteem, we may be excited by the differences we see in the other, as long as we remain attracted in some way. When chemistry wanes in a highly complementary relationship, each partner may wonder what they are doing with the other and drift apart.

Too much compatibility equals too much sameness which can turn into competition and boredom. Too much complementarity means too many differences which can turn into alienation. Either way, the relationship is in crisis when the flame of love is out and the civility of respect has been worn away. What differs is what the fights are about. When the partners become aware that this is happening, there is a choice to renew the relationship on a different footing, or separate, or drift in a grey zone of discontent punctuated by what Esther Perel calls “low level guerilla warfare.” For the relationship to survive, the partners must move from the confluence of new love to the cooperation of what Stan Tatkin calls a two-person psychological system, or in terms of Ellyn Bader’s developmental model of couples, from the stage of symbiosis to the stage of individuation while staying a connected as a couple.

Partners may experience too much compatibility, and the relationship may begin to feel boring or competitive:

... or too much complementarity, which can result in feelings of being misunderstood, judged, and invalidated.

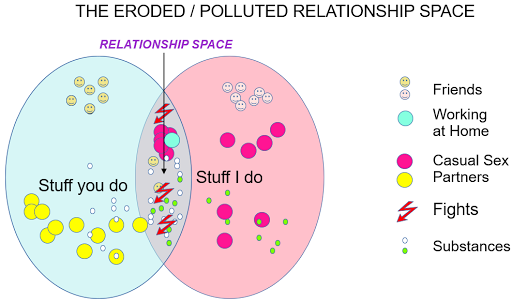

THE RELATIONSHIP SPACE

The relationship space is another useful concept consisting of two parts, one physical and the other psychological. The physical relationship space is where we are together, our nest, our home or the places we hang out if we don’t live together. The psychological relationship space is the inter-subjective realm where I believe the way I see us and the world substantially overlaps your subjective realm, and we both believe this union is highly unique in ways central to our senses of personal identity. To be vulnerable enough to let you in, I have to believe that we understand each other in this highly personal way. The psychological relationship space is the collision of our individual senses of self, split or damaged as it may be, our attachment histories, cultural identities, our emotional dynamics, our neuropsychobiological makeup and our neurotic defences, and possibly our psychological disorders and pathologies. It also includes agreements that we make with each other that define what the relationship is, what it is about and its boundaries.

The process of a couples drifting apart is the desertification of the psychological relationship space. The emotional oasis has become sand and the well is dry. Meanwhile the relative constancy and stability of the physical relationship space helps maintain the illusion of normality that is the hallmark of stable ambiguity. When fights do not cross the threshold where one can say with confidence, I’m better alone than with you, the existence of a relatively intact physical relationship space may keep the emotionally estranged partners in the relationship and keep them from confronting deep fears of being alone, rejected and unconnected.

WHAT HAPPENED?! THEY WERE SO OK TILL THE DAY IT ALL FELL APART

This post is about actions of the partners that threaten the relationship space, initiating the final crisis that will either drive them to repair the relationship or repair to separate lives. When all that is left is the shell of the relationship represented by the physical relationship space, the end can come quickly when someone creates a That’s it! I’m done! moment for the other.

Terry Real in his Relational Life Therapy speaks of the boundary of primacy around the relationship, that border that in respecting the specialness of the bond blocks incursions from outside. Stan Tatkin calls these intruders thirds: affair partners, casual sex partners engaged with outside of agreements with the primary partner, drugs, alcohol, gambling, intrusive friends, meddling relatives, demanding bosses, workaholism, sports or partying engaged in compulsively, children that are encouraged to be attention seeking or prevented by parents from becoming self-reliant. Thirds trespass on either the physical or psychological relationship spaces or both, such as the friend that regularly shows up and invites himself to stay for drinks or dinner, depriving the couple of reconnection time.

A subtle kind of third is parental transference1 onto the partner. (This kind of transference could be with respect to some other significant figure in their childhood).

Fighting ruptures the psychological relationship space and may drive partners out of the physical one. Fighting cuts across several of the five losing relationship strategies identified by Terry Real: needing to be right, controlling the other, unbridled self-expression, retaliation and withdrawal. In a similar vein, John Gottman identifies the four horsemen of the apocalypse (divorce): criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling.

Couples living in stable ambiguity know deep down that their situation is precarious. Perhaps in their families of origin nothing was quite real until someone mentioned it. In their relationship neither dares mention that the train engine has separated from the carriages as they roll down the slope. Fearing the emergence of conflict, the partners may evade engagement by coming home late, or, when at home, by indulging in work brought home, social media, getting stoned or drunk, or indulging in process addictions such as video gaming or online shopping. The risk rises as the only thing they have left as a couple, the physical relationship space, is bit by bit eaten away or polluted by some action involving thirds or fights.

It may elude one or both that activities involving thirds that they have agreed to permit each other outside the home or outside the awareness of the other are not acceptable at home or in the face of the other. Poor agreements or no agreements may have fostered these intrusions into the relationship space, or there may be an arrogant entitlement to do whatever wherever each pleases, or a vindictive desire to hurt by doing something one knows will be offensive to the other.

The pollution of the relationship space may be abetted by stress external to the relationship in the individual lives of the partners: job stress or job loss, financial problems, unmanaged illness, and in the present context, prohibition of activities outside the home by public order during the pandemic.

Some couples continue to hurt each other beyond the point where logically it makes sense to call it quits. The drama has gone on so long that the partners have become family to each other. Even though I know your reaction will drive me crazy, you are the only person I can turn to in crisis...the only one who will understand my emotions. The inter-subject sense of us has become a protective sense of family but it is contaminated by hostile dependence.

The work for the partners, which likely will require the guidance of a counsellor, is to:

-

get crisp on the agreements. If there are none, make some, especially house rules.

-

get a handle on substance abuse, process addictions and untreated mental illness

-

restore the sanctity of the home, the physical relationship space by cleaning it up and clearing out thirds

-

set boundaries with people who are not respecting the boundary of primacy of the relationship, and terminate relationships with those who will not cooperate in this

-

reduce stress in the wider context or at least acknowledge the influence it has

-

draw a line in the sand that leaves old hobby-horse arguments behind and out of bounds for further wrangling (e.g., You don’t care about what matters to me! You know order matters to me but you’ve lived in this house for 20 years and still don’t know where things go! OR I’ll never forgive you for the way you treated my mother on our wedding day!) Both partners know what the other thinks about the issue and no amount of discussing it has changed anything nor likely ever will. Let it go.

-

own projections by recognizing when the other partner is symbolically standing in for a parent or family-of-origin member with whom one has unresolved issues

-

place a moratorium on fighting, outlawing the four horsemen and the five losing strategies

-

never discuss sensitive issues when it is not possible to look into the eyes of the other at close range, definitely not in the car, by text or email or in the next room, with raised voices or when not sober, or when ill or tired

-

replace fighting with naming problems and resolving them in the frame of not putting the relationship on the line

-

work on one problem at a time

-

keep focused: working on a joint problem is not an occasion to criticize the other or make the problem into a character fault of the other. You and your partner may have a problem, but neither of you is the problem.

-

use proper time outs if things get heated. As Terry Real points out, a time out with no agreement when a resumption of talks will take place is not a time out at all; it is an evasion or might feel like one to the partner being asked to agree to it.

-

If you must argue, never do so for more than 20 minutes (after which the emotions are encoded in long-term memory)

-

re-find the common ground, the inter-subject sense of us

-

see differences (complementarity) as additions to the common good, not as threats

-

bring humour and tender moments back in to the relationship. As Terry Real says, everyone deserves a cherishing relationship.

-

redefine what the relationship is about and what kind of future the partners want together, a common relationship vision

This is not an exhaustive list, but if the partners are not successful on the majority of these points or cannot calm things down to an armistice during which change can be negotiated, they may be heading for break-up. The crisis at home occasioned by pandemic restrictions can be seen as the last straw or it can be seen as a wake-up call to attend to long simmering issues that were allowed to grow by ignoring them.

SUMMARY

This article has highlighted issues that simmer in many relationships and families living together. When one can leave for the day, be with others elsewhere, participate in individual creative or athletic activities, blow off steam in some other situation than the primary relationship, procrastination or repression of relationship problems is possible. With the added external pressure of pandemic restrictions on relationship partners and other family members, these internal issues are more difficult to ignore or defer. In attempting to cope with pandemic restrictions, the relationship space -- psychological and physical – may be further polluted by the introduction of “thirds” and by quarrelling, pushing things to the breaking point. These intrusions into the relationship space may not be recognized as efforts to cope with the added external stress perhaps, making the relationship seem more lost and hopeless than it really is. All relationships exist in some kind of context. Changes in that context must not be ignored in weighing what is going on in one’s primary relationship.

This discussion has been worded inclusively to acknowledge that not all relationships are dyads and may differ on several dimensions including the gender identity of partners.

REFERENCES

Bader, Ellyn & Pearson, Peter (1988) In Quest of the Mythical Mate: A Developmental Approach To Diagnosis And Treatment In Couples Therapy. Florence, KY: Brunner/Mazel.

Gottman, John, & Silver, Nan (1999) The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Perel, Esther. (2006) Mating in Captivity: Reconciling the Erotic and the Domestic. New York: Harper-Collins.

Real, Terrence (2008) The New Rules of Marriage. New York: Ballantine.

Solomon, Marion & Tatkin, Stan (2011) Love and War in Intimate Relationships: connection, disconnection and mutual regulation in couple therapy. New York: Norton.

Steele, David. (2006) Conscious Dating: Finding the Love of Your Life & the Life That You Love. The Relationship Coaching Institute.

FOOTNOTE:

1Parental Transference onto the Partner: This is an aspect of what Terry Real calls the Core Negative Image (CNI) each partner has of the other. It starts out with one being attracted to the other by an unconscious recognition that their family-of-origin dynamics are similar. They recognize this commonality in each other. In effect they are attracted by each other’s “relationship baggage.” Unconsciously they choose each other to work out unresolved issues with one of their own parents (or other pivotal family member). As the novelty of a relationship wanes and problems inevitably emerge – amplified in the hot house environment created by pandemic restrictions -- each partner emerges as a surrogate for their parent or family-or-origin member with whom they have unresolved issues. Their irritations with each seem present day, but gain their emotional charge from from childhood experiences. In time each may pick up the role projected onto them, and they begin to behave even more like the other partner’s parent (projective identification) thus augmenting the deadly embrace of this enmeshment. The relationship is not a relationship so much as it is an experiment. The logic of the experiment is that if I can solve my family-of-origin conundrum with a surrogate (in the form of my partner), I will be free of the spell that issue has on me. (False) This makes the relationship not about relating, but about winning some battle for identity and recognition. There is a narrow chance that the gamble will pay off in an insightful untangling of the family-of-origin Gordian Knot without blowing up the relationship, but more often than not, the relationship is sacrificed to the experiment. For example:

Alice’s father had a warm and generous side she wanted him to extend to her but seldom did, always having more time for her brothers. Her protests about not being treated fairly only served to increase her alienation in the family. She was seen as difficult and hard to please. Her mother sympathetically said she understood, but seemed powerless to influence her husband to be a more egalitarian father.

In her 20’s Alice met Sean. She was immediately attracted to his warm generous energy that seemed to include her, and he to her impetuous nature that reminded him of his mother whom he described as demanding but caring. In his early teens Sean’s parents had divorced, an event that shattered his life, seldom seeing his mother after that. He was raised by his father, a man a lot like Alice’s father.

In time Alice and Sean had two children with whom Alice found herself spending most of her time while Sean became increasingly involved with his work and male colleagues and friends. She felt left alone to manage their domestic life single-handedly. Although she complained to Sean about the inequity of this, he would silence her protests by saying that he was providing for the family. To her, it was all happening again: as a woman, being undervalued by the most important man in her life. To him, it was also all happening again: being “controlled” by a woman who like his mother was never satisfied.

The baggage – a third -- Alice and Sean brought into their relationship was the need to mend attachment wounds from their families of origin. In recognizing one or both of their parents in each other, they unconsciously re-enacted their family of origin dynamic to hopefully play it out more happily than it had growing up. We leave their story at the point of stable ambiguity with each resenting the other, giving up on speaking about their problems except for the odd bit of sniping. This is the vulnerable juncture that is the topic of this this paper: the marriage might falter and fail with additional pressure on it, or it can move to a new healthier level if Alice and Sean manage to see what they are doing and have the will to move beyond it.